An Architectural Legacy Remembered and Preserved

By John A. Dalles

Preface: The Wikipedia article about Isabel Roberts is the compilation of my research about her life and work, which I began in the early 2000s. I created the Wikipedia page and more than 95% of what appears in it is the result of my research over nearly 20 years.

When I began the research, almost every Frank Lloyd Wright expert, scholar, and writer believed the red herring that Wright told Grant Carpenter Manson in the 1940s, specifically, that Isabel was merely the secretary, bookkeeper, and general factotum in the Oak Park Studio. As a result of my research, it is now universally acknowledged that while she did perform those duties, they are not the whole story; Isabel was an architect in her own right and practiced architecture both in Oak Park and in Orlando, Florida. A matter attested to by Wright himself, who wrote about her that she was an 'Architect', with a capital 'A'.

I have chosen to post my initial research here, and to add to it when more information is brought to light. And there is always something new to be learned.

I invite architectural historians of today not to make the same mistake as those of the past, and to delve even deeper into Isabel's accomplishments as one of the earliest women architects in the USA.

Now, sit back and enjoy a truly remarkable story...

Isabel Roberts (born March 7, 1871 in Missouri) was a Prairie School figure, member of the architectural design team in the Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright and partner with Ida Annah Ryan in the Orlando, Florida architecture firm, “Ryan and Roberts”.

For most of the 20th century her creative output went unrecognized. When I received the book "Frank Lloyd Wright: Hometown Architect" by Patrick F. Cannon, my research into the work of Isabel Roberts in Central Florida began. In the book, Mr. Cannon states that Isabel Roberts was an architect in her own right and after her Illinois years, was in practice in Orlando, Florida. This was the impetus for me to do more research on the matter, since I was living in Orlando, and very much interested in the historic architecture of Central Florida.

Over the next decade and more, I delved into the life and work of Isabel Roberts, and discovered that she had formal training in architecture, had a design role in the Oak Park studio, and designed some of the most iconic homes and public buildings in Central Florida during the 1920s.

My first foray into putting my work in printed form for others to read and expand upon was the Wikipedia article about Isabel Roberts, which I initially posted, more than a decade ago, and added to over the years. While I may choose to do more revising of it, as more information comes to light, I feel it is important to share here on my blog, not only what I have discovered about Isabel and her contemporaries, but also to provide a place where I can indicate what further research is warranted.

There is plenty of both to share.

My hope about this is threefold.

First, that the community of architectural historians, now and in the future, come to acknowledge Isabel as an architect / architectural designer, without objection or reservation.

Second, that those who own or have some responsibility for structures designed by Isabel - primarily in conjunction with Ida Annah Ryan - protect and preserve them to the utmost of their ability.

And third, that Isabel finally receives the attention she properly deserves, as one of the pioneering women in the field of architecture in the United States of America.

Her story is of great interest to anyone who has appreciated architecture in the so called prairie style, as well as architecture reflecting the "Spaniflora" style so prevalent in Central Florida in the 1920s.

Childhood

Isabel Roberts, was born in Mexico, Missouri on March 7, 1871, the younger of two surviving daughters of James H. and Mary Roberts. This fact is undeniable, and it stands in contrast to the other erroneous conjectures about Isabel's family which are found in some standard works on Frank Lloyd Wright, and in comments on "Wright Chat", and elsewhere.

Many architectural historians of the past got their facts entirely wrong. Isabel was not (as some have claimed) related to any of the various other persons with the last name of Roberts who were clients or neighbors of Frank Lloyd Wright in Oak Park. Many architecture scholars have misidentified Roberts' parents; mistakenly stating that Wright's client Charles E. Roberts was her father. He was not. (See for example of the perpetuated error: The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, by William Allin Storer, Second Edition, p. 150).

Isabel Roberts' father, James H. Roberts was the son of William and Sarah Roberts of Utica, New York. Charles E. Roberts was the son of David and Elizabeth Roberts. Charles E. Roberts and James H. Roberts were not siblings, in fact, no family connection has been found between these two men. If you read that mistaken information, or similar, mentally correct it.

Nor was Isabel Roberts related to the architect Eben Ezra ("E. E.") Roberts, a native of Boston, who grew up in New Hampshire before relocating to Chicago to work for Pullman in 1893. Again, any references to a family relationship between E. E. Roberts and Isabel Roberts is erroneous, and needs correcting.

I encourage those Wright scholars who are still living to fix their mistake in this matter, whether in their books, their websites, or as aforementioned "Wright Chat". By now, so much correct information about Isabel and her family has come to light, that their error is obvious as such. So please fix it. Otherwise your readers will be reading fiction, not fact.

Much factual information is known about Isabel Roberts' parents, which I will supply here:

James H. Roberts (July 26, 1841 [per a tribute published at the time of his death] or 1842 [per his gravestone] – February 9,1907) was a mechanic and inventor born in New York. He held patents for his industrial designs. He went on to hold important positions in several states. As is noted below.

Mary Harris Roberts (December 29 or 31, according to obituary vs. cemetery records, 1836-August 16, 1920) the daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth Glover Harris, was a homemaker and a native of Prince Edward Island.

More about Jame H. Roberts: James was lining in the home of John Roberts in 1860, his occupation given as "machinist".

James Roberts and Mary Harris were married on June 10, 1867 in New York. By 1870, according to the US census they were living in Salt River Township, Audrian County. Missouri. With them was their daughter Mary, age 1, born in Missouri.

Soon after, they relocated to Mexico, Missouri, where their daughters Charlotte and Isabel were born (one family history says Brookfield, Missouri, which is 100 miles northwest of Mexico, Missouri). Charlotte Jeanette was born May 18, 1870, and died at St Cloud, Florida May 21, 1933). She married John Somerville, of whom more, later. Isabel (aka Isabella) was born March 7, 1871, and died in Orlando Florida, December 29, 1955.

(Note that they no longer counted a daughter Mary in their household; presumable the child had died).

Early records show Isabel's name spelled as Isabella, Isabell, Isabelle, or Belle, before she settled in, using the form of Isabel. This is important information for those who seek to research her early years. She was named in honor of Mary's sister, Isabel Harris. Charlotte was named in honor of James' sister Charlotte J. Roberts Lewis, (July 1825-died after 1925, married Martin Lewis, both of Utica NY).

After leaving Missouri, the James and Mary Roberts family moved several times, including to Providence, Rhode Island, which is where they lived at the time of the 1880 United States census. Their address was 87 West Reven (sp?) Street. At the time of that census, Charlotte was 11 and "Isabella" was 9; both were listed as "at school". James was listed as a "machinist". Isabel is listed there as having been born in 1871. Her birth state is given as Missouri.

By the time of the 1900 US census, the Roberts family were living in South Bend, Indiana. James is a machinist, "Lottie J" is a school teacher, and "Isabell" is "at art school", which is of course, as will be discussed below, the Atelier Masqueray-Chambers, in New York City.

After working for the Oliver Chilled Plow company, in South Bend, James H. Roberts accepted an important role as the Deputy Director of Inspections for the State of Indiana. This meant that Roberts was in charge of inspecting manufacturing plants in the entire northern half of the state. This was a job that placed him in a highly visible and prominent executive role.

Mary's brother, John D. N. Harris (1858-after 1905) was also a resident of South Bend, as recorded in the 1905 obituary of James Harris (their brother, of New Hartford). Whether he preceded or followed James and Mary Roberts to South Bend is not yet known.

While living in South Bend, the Roberts family were quite active in church and civic groups. Mary, Charlotte, and Isabel were all members of the First Presbyterian Church of South Bend, Indiana, as were many other prominent citizens including the Studebakers, the owners of the Oliver Chilled Plow company, and most notably, Nelson Prentice Bowsher and Laura Caskey Bowsher. All of whom were near neighbors of the Roberts family.

(Author's note: I served as associate pastor of that same church in the years 1982-1987. Many descendants of these families were my parishioners. The church's rolls record the Roberts' membership there. It was at my urging that these records were discovered in the church vault, by my friend, Professor oof History Les Lamon).

A description of the sisters comes from their second cousins Bill and Sarah Hogoboom: "Isabel was tall and thin; Charlotte was short and fat (as we know from their passport applications)."

Naturally, the Roberts became friends with their neighbor and fellow church member Mrs. Nelson Prentice Bowsher, the industrialist's second wife, who was a generation younger than her husband, and roughly the same age as his grown children. Laura Caskey Bowsher (later, DeRhodes) was a dear and trusted friend of Isabel Roberts. This friendship eventually led to Isabel’s introducing Laura to Frank Lloyd Wright and Laura’s commissioning from him what has come to be known as the K. C. DeRhodes House.

During her high school years, Isabel proved to be skilled in artistic and domestic arts. In 1887, according to the Annual Report of the Indiana Board of Agriculture, Isabel won first place for her crochet mittens, and second place for her crochet work display at the Indiana State Fair.

Isabel graduated from the South Bend High School in the Class of 1890, and is pictured in the annual yearbook. This is one of only a very few photographs of Isabel that have come to light. At the time of this writing in May 2025, this is the first place it is shown other than the yearbook itself. Compared with the later photo that accompanies the first page of this post, Isabel is recognizably herself, but shown in the first bloom of adulthood.

Isabel ("Belle") Roberts - 1890 - Age 18

Sister Charlotte had graduated from the same high school two years earlier. We also have her senior graduation photo, thanks to that year's yearbook.

Following secondary school, Isabel eventually embarked upon a plan to become an architect. To further her education, she went east to New York City and there she enrolled in an innovative program of architectural study.

And here is presented to the researcher an area for further perusal. From the time she completed high school in 1890 until the time she was an architectural student in New York City in 1900, the question is this: Where was Isabel, and what was she doing?

Sadly, the 1890 US Census can offer researchers no insights, as most of these records were destroyed by a devastating fire, and those which survived the fire were destroyed by an act of Congress (one of the bonehead moves of a misguided bureaucracy!). Even so, there are some hints and leads worth researching.

It has been said that Isabel was an art teacher at some point in the years 1890-1900. This possibly seems to be consistent with her future vocation. No proof has yet been found to confirm this information.

However, we do have information that Charlotte graduated from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor with a Bachelor of Philosophy (PHB), in 1897. This information is to be found in "The Michigan Alumni" (1933) in which Charlotte's death is recorded. Her middle name, Jeanette, is provided in this same listing.

The Mystery of "Isabel Roberts JONES":

More intriguing is the quotation in Patrick Joseph Meehan's book "Frank Lloyd Wright Remembered" from FLW's son Lloyd Wright, who says: "Well, the draftsmen were all interesting individuals. There was [William E.] Drummond and Marion Mahony [Griffin], and the secretary, Isabel Roberts Jones, and so own and on and on. They took good care of me, as a junior member, and they helped me up on the stools make tracings of their glasswork for them."

This comment intrigued me, because Lloyd called her "Isabel Roberts Jones."

I contacted Patrick Meehan to ask if perhaps Lloyd had misspoken, and Mr. Meehan assured me that was exactly what Lloyd said and meant to say. So, this raises several questions.

In the years 1890-1900, is it possible that Isabel married someone named Jones?

Further, why would the name have been remembered so specifically as such by an immediate member of Wright's family, unless there was an important reason for it to be etched in the Wright family's collective memory as Isabel Roberts Jones?

Could it be that Isabel was at one time married to a member of the Lloyd Jones family?

If so, there seems to be only one likely candidate, that being Frank's first cousin Richard Lloyd Jones. All the many biographies of Richard Lloyd Jones record only his marriage to Georgia (always known as 'George") Hayden. Richard would have been 34 when they married; certainly a tad old for a first marriage, then or now.

More research is needed. Possible avenues of exploration include news articles from the cities where Richard Lloyd Jones was employed prior to settling in Madison, Wisconsin, and the annual records of his father's congregation, which always stated the names of those persons whom Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones married.

Evidence of Richard Lloyd Jones having been married prior to his marriage to Georgia Hayden is found in the 1906 "Annual of All Souls Church". Mr. and Mrs. Richard Lloyd Jones are listed as out of town members. They were living in Nyack-on-Hudson, New York in 1906. For reference purposes, Richard Lloyd Jones married Georgia Hayden of Eau Claire, Wisconsin on April 30, 1907.

Wherever Isabel was and what she was doing in the last decade of the nineteenth century, we know with certainty that by 1900, she was living in Manhattan and studying architecture at the Atelier Masqueray-Chambers.

The documentation is the US Census of 1900, in which Isabel appears as shown on the actual enumeration page, below:

In addition, she was "counted" a second time in the 1900 Census, in South Bend, along with her parents and her sister. There, she is 28 years old and "at art school" and her sister Charlotte's profession is "teacher". Of course, the art school in question was the Atelier Masqueray-Chambers in Manhattan.

In the Atelier Masqueray-Chambers

Franco-American Emmanuel Louis Masqueray (1861-1917) was a preeminent figure in the history of American architecture, both as a gifted designer of landmark buildings and as an influential teacher of the profession of architecture.

Later generations of architectural historians have fallen prey to the simplistic view that the only architecture worthy of consideration between Wright and the emergence of the International Style was none of it whatsoever. So Masqueray has been mainly forgotten. Even if he had not worked on the projects he designed, even if he had not served in the architectural practices in which he served, he should be remembered for the over-arching achievement of establishing - for the first time in the United States - an atelier along the exact lines of the French Ecole des Beaux Arts. A cursory glance at the names of those who were trained in his atelier is like a veritable who's who of successful architects of the mid twentieth century. And those who would underestimate the value of an atelier education for architecture must tread ever so carefully, since the great man himself, Frank Lloyd Wright, established the same sort of architecture school along the atelier lines, at Taliesin. If one were to discount the teaching efforts of Masqueray, one would also therefore have to discount the teaching efforts of Wright.

It is just that simple.

Masqueray had been born in Dieppe, France, on September 10, 1861.

Masqueray came to the United States in 1887 to work for the firm of Carrère and Hastings in New York City. Five years later, he joined the office of Richard Morris Hunt. In Hunt's firm, he helped design many notable buildings including The Breakers for Cornelius Vanderbilt II in Newport, Rhode Island.

In 1893, Masqueray opened the Atelier Masqueray, for the study of architecture according to French methods; architect Walter B. Chambers shared in this enterprise. Located at 123 E. 23rd Street, this was the first wholly independent atelier opened in the United States. Research has revealed that among his students over the next decade in New York were:

- Leonard B. Schultze (architect of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in NYC)

- Walter W. Sharpley (builder of Philadelphia's Bellevue-Stratford Hotel)

And perhaps the most important of Masqueray’s students…

- William Van Alen (architect of the Chrysler Building)

You will find a much longer list that I have amassed in my research, which forms the body of the Wikipedia article about Masquery. Of course, the list will grow as more becomes known. Here it is:

This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

- Paul R. Allen (architect of Henry Miller's Theatre, NYC)

- William T. L. Armstrong (later of the firm De Gelleke and Armstrong, New York)

- W. Bellows (architect Charles Walter Bellows of Columbus, OH)

- William Berger

- Guy Bolton (Broadway impresario)

- Charles Saunders Bridgman (1892-1897 Atelier Masqueray; then practiced with C. A. Rich; then 1903-1937 in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada)

- Seymour Burrell (architect of the St. Germain Lofts, Houston, TX; S. H. Kress & Co. Corporate Architect)

- James E. Cooper (of d'Hauteville & Cooper, Long Island architects); Greentree, William Payne Whitney Mansion.

- Lester A. Cramer (later practiced in Los Angeles; architect of the Rosicrucian Fellowship Temple and the Sanatorium[at Mount Ecclesia)

- Roy Corwin Crosby (architect of houses on the Palisades)

- Clarence E. Decker (later of Decker and Stevenson, architects of the YWCA, San Diego)

- Mortimer Foster (later of Foster, Gade and Graham)

- Frederick George Frost, Sr. (principal of his own firm in New York City which later included his son and namesake), Hall of Fashion, New York 1939 World's Fair

- Leon N. Gillette (of the NYC firm Walker & Gillette)

- Nelson Goodyear (architect and inventor)

- Mr. Gray (no first name given)

- William Cook Haskell (later of the firm Townsend, Steinle & Haskell)

- James Hopkins (of the Boston architectural firm of Kilham and Hopkins)

- John G. Hough

- William S. Hutton (later an Indiana school architect who partnered with George Grant Elmslie)

- Louis Jallade (architect of the gymnasium at the University of Delaware)

- John R. Jordan

- Rupert W. Koch (architect of men's dorm at the University of Michigan)

- Frederick Larkin (later of the US State Department in charge of Embassy design)

- Mr. Loud (no first name given)

- Louis Levitansky (later "Louis Levine") - Westchester County NY architect

- Charles E. Mack (associated with the firm of Cass Gilbert)

- Sylvester S. McGrath (later of the firm Davis, McGrath & Kiessling, architects of among many others, Gramercy East Professional Building, 115 East 23rd Street, New York City)

- Henry Murphy (architectural advisor to China)

- George Nagle (associated with Masqueray at the St. Louis Fair)

- Clarence A. Neff (later of Neff and Thompson, Norfolk, VA)

- Charles F. Owsley (principal of a Youngstown, OH, firm; designed the Art Deco Isaly's headquarters there)

- Barnet Phillips, Jr. (later of the firm Barnet Phillips Architectural Decorators, New York)

- Karl Richardson

- Isabel Roberts (of the Oak Park studio of Frank Lloyd Wright)

- Lincoln Rogers (of the 1920s firm Rogers and Stevenson, in San Diego)

- Frank B. Rosman

- Mr. Schalkenbach (no first name given)

- Leonard B. Schultze (architect of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel see Schultze and Weaver)

- Walter W. Sharpley (builder of Philadelphia's Bellevue-Stratford Hotel)

- Francis S. "Frank" Swales (later of the firm Painter & Swales; designer of Selfridges' Store, Oxford Street, London, and The Brussels Exposition of 1910's Canadian Pacific Railway Pavilion)

- George E. Sweet (who became a naval architect)

- William Van Alen (architect of the Chrysler Building)

- Elwood Williams (associated with Masqueray for the St. Louis Exposition; later with offices at 507 Fifth Avenue, NYC)

- Edward J. Willingale (associated with J E M Carpenter as architects of the Lincoln Building (42nd Street, New York, New York) now known as One Grand Central Place)

- Wilison Joseph Wythe (assistant professor of drawing, University of California)

It is an impressive list, indeed.

In 1897, Masqueray left the Hunt office to work for Warren & Wetmore, also in New York City.

Masqueray’s reputation became international in 1901, when the commissioner of architects of the St. Louis Exposition selected him to be Chief of Design. As Chief of Design of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, a position he held for three years, Masqueray had architectural oversight of the entire Fair and personally designed many of the Fair buildings.

In 1904, Masqueray was invited by Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul to come to Minnesota and design the new Cathedral of Saint Paul in Saint Paul for the city. Thereafter he designed more than a dozen landmark churches and cathedrals in the upper Midwest, where he is best remembered and appreciated today.

Isabel received excellent training at the Atelier Masqueray-Chambers. However, by the time that Isabel submitted her application to the AIA for membership, in 1920, Masqueray was no longer living, and as a result, unable to attest to her three years of architecture training at the Atelier Masqueray-Chambers in New York. Also, by that time, an anti-atelier movement was gaining preeminence in the views of the AIA, in favor of architectural departments at colleges and universities. Such a bias continues today in the minds of architectural historians who forget that the training for the profession of architecture in the early 1900s found apprenticeship, ateliers, and college departments all brining skillfully trained architects into the profession.

Oak Park, Illinois

Upon her return to the Midwest, Isabel Roberts was among Wright’s first employees when he left Louis Sullivan and opened his own studio in Oak Park, Illinois.

A clear understanding of Isabel Robert’s role in the Oak Park Studio comes from Wright’s son, John Lloyd Wright, who outlines the contributions made by Miss Roberts and other figures of the Prairie School. John Lloyd Wright relates that William Drummond, Francis Barry Byrne, Walter Burley Griffin, Albert McArthur, Marion Mahony, Isabel Roberts and George Willis were the "draftsmen". He further clarifies that they made up "the five men and two women who each were making valuable contributions to Prairie style architecture for which" Wright became famous.

Notice how carefully John enumerates that there were seven draftsmen, five men and two women (Marion and Isabel). This is compelling evidence that Isabel Roberts provided a greater contribution to the Prairie school architecture than scholars have given her credit, heretofore. Isabel Roberts has been described by Wright scholars as Frank Lloyd Wright’s secretary, bookkeeper or office manager. While Isabel certainly fulfilled these functions, she also took an active role in the lively and creative design atmosphere of the Studio. Contemporary witnesses acknowledge that Isabel had a hand in design, although most do not give her anything near the proper credit she deserves in being a draughtsman for Wright.

Oak Park Studio architect Barry Byrne describes the informal competitions that Wright held in the Studio among the employees, to design residences as well as the details of a project: stained glass, murals, mosaics, linens and furnishings. The staff designed entire plans and elevations. The various solutions would be considered and critiqued by one and all. Byrne recalled that more often than not Marion Mahony Griffin was the winner of these intramural competitions. Not allowing good ideas to go to waste, Wright filed away all of the results of the competitions for future use as new clients came to the Studio. Byrne confided that Wright took the credit for all these designs, no matter whose they were to begin with; he also asserts that Wright severely chastised anyone who referred to any of the designs as being by any of the Oak Park Studio employees, rather than Wright himself.

Those who have worked in architectural firms will understand that very little has changed since that time, more than a century ago. The principal or principals of the firm take the credit no matter which other architects on staff designed the work. Added to that was Wright's well-known penchant for aggrandizing himself to the detriment of his associates. This tendency was present even in the early successes of the Oak Park Studio years, and would become pronounced almost to the point of ridiculousness by the end of Wright's very long life. He erased the contributions of others, and because he long outlived most of them, there was no one to correct him. Unless of course you read Marion Mahony Griffin's autobiographical tome "The Magic of America", in which she records the impact of Walter Burley Griffin on the innovations of the Prairie School era, which she called "The Chicago Group". This work has never appeared in print, but it is available to be read in its entirety on line, and I encourage interested persons to do so. Every Wright scholar worth their salt should. Marion was so unhappy about Wright's lack of acknowledgement of the work of his associated architects, that she never mentions him by name in the entire autobiography, calling him only, "the architect".

Wright could have taken a different approach. Looking at the group of associated architects and their subsequent accomplishments, not to mention their contributions to the success of the Oak Park Studio, Wright could have said something along the lines of this: "Aren't I a tremendous judge of talent, to have attracted to my firm this marvelous group of people who under my supervision, helped to create a truly distinctive American architecture!" How much better than to pretend he did it all by himself and that all they did was push pencils in the lines he had predetermined.

Implications of the normal working style of the team of architects and architectural designers in the Oak Park Studio are many, and warrant further scholarship.

Think what this means; about the output of the Oak Park Studio during that decade of stunning creativity between 1898 and 1909.

Barry Byrne does not say, "From time to time one or another of the professionals working with Wright came up with an idea that Wright incorporated into his design." No, Byrne DOES say that all of the architects offered their designs, discussed their designs, and then one of their designs was selected to be developed. Trusting that what Barry Byrne said is true - and there is no reason to doubt it - one could then look at all of the buildings of that time period as collaborative efforts of this kind. Even more accurately, one could look at them as the realized collection of the ideas of each of the architects in the office.

When this normal working practice of the Oak Park Studio is taken to any number of logical conclusions, one can say these things about the Prairie Style that emerged from the Oak Park Studio:

One: There was a lead designer for each building. It may have been Wright, it may have been one of the others working in the office. This was the rule, not the exception.

Two: The design ideas presented in these buildings are so varied within the theme, that what might have appeared to be experimentation from Wright only, might instead be considered the development of favorite ideas of each of the individuals in the Oak Park Studio.

Three: In looking at the work of each of these architects after they left the Oak Park Studio, one possible conclusion is that the designs one sees in their independent practice are a continued development of the ideas that they presented and they implemented, in the Studio. This is not the only conclusion of course. Another could be - that they saw something in the work of others in the studio that they wanted to develop on their own. That could mean that “someone” was Wright, or that "someone" was any of the other architects in the studio.

Four: Continuing on the theme of the variety that was produced. This begins to help us understand why there are collections (sub-groups) of Fran Lloyd Wright's Oak Park Studio era residences that have certain similarities, or marked differences. For example there are stucco faced houses, there are board and batten faced houses, and there are Roman brick faced houses. The accepted wisdom said that the setting, or the budget, decreed which of these was used. And of course the taste of the client might have something to do with it as well. But another equally plausible possibility is that certain of the Studio architects preferred one medium, while other architects preferred another. The same would be true of the variety of heights, the three story houses are usually not emphasized, or they are talked about as an experiment that was tried but never fully developed. But could it be that one of the staff was very fond of that concept, and from time to time that staff member’s ideas prevailed in the group discussion? There were flat roofs, hip roofs, gable roofs. The design devices utilized could be further scrutinized.

Five: While the assumption that Wright came up with every single idea on his own is remotely possible, it’s highly unlikely.

Six: A careful study of the designs of each structure that came out of the studio during that period would offer a keen observer an opportunity to trace the hand of this, that, or another individual via the design elements that are seen in these buildings. This would not be an idle exercise.

Seven: If we combine what Barry Byrne says about the shared input of all the staff, with some of the clues that Marion Mahoney gives us in her autobiographical work, “The Magic of America”, we’re given a roadmap for at least one of the designers in the studio, that being Walter Burley Griffin. Marion specifically states that Walter designed the Frank Thomas House in Oak Park (by Wright's own definition the first Prairie house), she describes why it is sited on the lot the way it is, and claims it is the first L-shaped plan house. There’s no great reason to doubt what she says.

Eight: To ascribe the origin of buildings to individual designers in the Oak Park Studio does not take away from what we consider to be the genius of Frank Loyd Wright. Indeed, it expands upon it.

Nine: These newly highlighted but century-plus-old insights regarding the daily practice in the Studio invite serious academic scrutiny.

Ten: It is not inconceivable that in future one could speak of the “Marion Mahoney Influence“ or the “(fill in the other Studio employees names) influence”.

Oak Park Studio Employees-1898-1909

Architectural Designers / Draughtsmen:

Marion Mahony - 1895-1910

George Willis - 1900-1904

William Drummond - 1901 (or earlier)-1909

Walter Burley Griffin - 1901-1906

Clarence Erasmus Shepard - 1902-1905

Andrew Willatzen - 1902-1906

Barry Byrne - 1902-1907

Isabel Roberts - 1903 (or earlier)-1909

Charles E. White, Jr. - 1903-1905

Cecil Bryan (mistakenly called Cecil Barnes) - 1904

Marion Chamberlain - circa 1904

Harry Franklin Robinson - 1906-1908

Albert Chase McArthur - 1907-1909

Francis Conroy Sullivan - 1907

Robert Hardin - 1906-1909

Charles Erwin Barglebaugh (3 years) - 1907-1909

Taylor Wooley - 1909

John Van Bergen - 1909 (widely noted as last to be hired)

Artists in Residence / Furnishings Designers:

Maginel Wright

Richard Bock - circa 1904-1909

George Mann Niedekin - circa 1904-1909

Business Manager / Design Specifications:

Arthur Tobin - 1906-? (Wright's brother-in-law)

Before expanding upon the work that Isabel did in the Oak Park Studio, it is important not to miss several facts. Her training in New York being the most compelling evidence for the contributions she made to the architectural collaboration of the staff. It is also widely reported that she was quietly efficient and alert to the work that supported the design draftsmanship of the firm, to the point that comments about her being a secretary, bookkeeper, general factotum, and so forth, were part of her job. But not all of it, and not the main focus of her work.

It is also known that Isabel Roberts was included in the family lives of Catherine Tobin Wright and Frank Lloyd Wright in ways that other employees were not. She, for example, was called upon to babysit the Wright children when Frank and Catherine were out of the house for social gatherings.

The Oak Park Public Library and the archives at the Home and Studio both have a photo that Wright took of his family gathered alongside the front wall of their home. To the right, one can see Catherine, with John Lloyd Wright in front of her, and Lloyd Wright (FLLW Jr) to his right. One must look with sharp eyes to see that between Catherine and Lloyd there is another woman pictured. She is looking down at John. The photo is such that she almost blends into the shrubbery behind her.

John Lloyd Wright identified all of the people in the photo, and he identified this figure as Isabel Roberts.

(above - Detail of photo below)

So, what was Isabel Roberts' influence in the Oak Park Studio in the years 1903-1909? What work did she do? What design contributions were hers?

It is known that Isabel produced original designs for the leaded art glass windows in the Prairie houses during this period. How do we know this? Charles E. White Jr writes, "Miss Roberts works most of the time on ornamental glass..." Charles E. White, Jr. Letters, 1903–1906, by Charles E. White, Jr. from the Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright. The archivists at Taliesin are unable or unwilling to attribute any drawings to any particular person, and many of the original drawings were said to have been lost in one of the several Taliesin fires. Even so, the records of an eyewitness contemporary Studio employee are proof enough that Isabel was part of the Oak Park architectural design team. (Notice what Charles E. White, Jr. does NOT say, "Miss Roberts works most of the time answering the phone, paying bills, and typing letters"!).

To try to get a perspective on where Isabel was living in the Oak Park years, this is what I have learned thus far. According to annual editions of the "Chicago Blue Book", in 1905 she was living at 505 Forest Avenue in Oak Park. By 1907, her address is listed as 405 Forest Avenue, Oak Park, continuing through 1910.. Her mother Mary has moved from South Bend to Maywood (no address given but probably the Isabel Roberts House, Maywood's boundaries included parts of what would become River Forest) by 1912. Throughout her appearances in the Blue Book that I have found so far, she is listed as "Miss Isabelle Roberts". Which was perhaps the spelling of her given name, later shortened to Isabel. Her residential locations are continuing to be researched.

The letters of Charles E. White, Jr. were written at a time when the following projects, and more, were underway: Darwin D. Martin House, Burton J. Westcott House, Mrs. Thomas Gale House, H. P. Sutton House, Robert M. Lamp House, and Unity Temple. The "light screens" in these houses may owe their design in part or in full to Isabel Roberts.

Some of the ornamental glass from this time period is shown below. It is known that Isabel designed the Sutton Residence light screens. There were at least five of the Studio employees engaged in the Sutton project, which demanded a great deal of time, and a maddening number of revisions, at the request of the clients. All documented in the Wright archives. A look at one Sutton light screen is shown below:

And it is probable that Isabel designed the Darwin D. Martin House light screens:

In addition to her undeniable contributions as stated by Charles E. White, Isabel herself stated in her 1920 AIA application that in her Chicago years, she designed the house for herself and her mother (yes, THE Isabel Roberts House in River Forest) and the house for her friend Laura Caskey Bowsher and her second husband K.C. DeRohdes in South Bend, Indiana. Wright was aware of and never disputed Isabel's claim.

From their South Bend days, Mary and Isabel Roberts were friends of Laura Caskey Bowsher, the lovely young second wife, and then widow, of industrialist-millionaire farm equipment manufacturer, Nelson Prentice Bowsher. Isabel introduced Laura to Wright, who seldom let a well-heeled potential client get away. This led to the commission for Wright to design a new home for Laura in time for her to move into it with her second husband, Kersey C. DeRhodes.

Laura Caskey Bowsher’s wedding to Kersey C. DeRhodes took place in the Chicago neighborhood directly south of Oak Park, Berwyn, Illinois, on September 22, 1906. Frank Lloyd Wright’s uncle, the celebrated human dynamo Unitarian minister, the Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones, officiated.

In plan, the DeRhodes house is a mirror image twin of the 1904 Barton House in Buffalo, New York. The main floor of the house is a graceful, generous rectangular space oriented south to north, subdivided by piers and low bookcases with light screens into three distinct zones: a reception hall, a large living room with fireplace toward the south (front) of the house and a large dining room with Wright's customary built in china cabinets toward the (north) rear of the house.

The exterior of the DeRhodes house exhibits many of the features associated with Wright's Prairie School architecture. The stucco exterior with dark wood trim, the strong water table, the pronounced horizontal lines of the continuous window sills and terrace parapets, the leaded glass "light screens" of the windows, the grouping of the windows into continuous bands and the low-profile hip roof.

The celebrated rendering of the DeRhodes house by Wright's associate, Marion Mahony Griffin, is considered by architecture scholars to be among the best to emerge from the Oak Park Studio, and was highly regarded by Wright himself, who inscribed it "Drawn by Mahony after FLLW and Hiroshige".

(In her AIA application, Isabel Roberts listed the K C DeRhodes house as her own work).

The following year, James H. Roberts died. This tribute was published in the Eleventh Annual Report of the Department of Inspection of the State of Indiana, 1907.

Death of Deputy James H Roberts

In the death of James H Roberts, Deputy Director, on 9 February, 1907, at his home in the city of South Bend, the state of Indiana lost one of her honored citizens, a man of high moral worth, his character in the community where he lived was regarded by all who knew him as pure and spotless. As a man, his aims, purposes, and daily life were high, honorable, and in the direction of right, as he could see the right.

In the discharge of his duties as a deputy inspector, his practical knowledge and experience from early boyhood in the mechanical field was most helpful to all concerned. In his work of inspection, Deputy Roberts was earnest and conscientious, and with his kindly disposition towards his fellow man, his return was always welcomed and looked for. In the hearts of all who had a good fortune to claim his friendship, Deputy Roberts will ever be held in great fall remembrance.

Here is one obituary notice placed at the time of James Roberts' death:

A longer memorial tribute to James H. Roberts was published in "The History of St. Joseph County", a transcript of which appears below;

Following James H. Roberts’ death, Mary Roberts moved to the Oak Park. Illinois, area to be near Isabel. While Isabel was in Wright’s employ, Mary and Isabel built a house together, which is known today as the Isabel Roberts House, in the Chicago suburb of River Forest.

Isabel Roberts House

A classic 1908 Prairie House from the studio of Frank Lloyd Wright located at 603 Edgewood Place in River Forest, IL. The Isabel Roberts House in River Forest, Illinois, was built for Isabel Roberts and her widowed mother, Mary Roberts.

The Isabel Roberts house is sometimes credited as being the first split-level house.

It is fair to say that the Isabel Roberts House is greatly admired by architects world-wide and regarded as one of the most innovative residences to have emerged from Wright’s Oak Park studio. The commonly held view among architectural historians is that the Isabel Roberts House was designed by Wright, for Isabel and Mary to share, which they did for a decade before leaving Illinois. However, in her AIA application, Isabel lists the Isabel Roberts House as being among the buildings she designed, one of three she gives as examples.

In late 1909, Isabel Roberts was among the last of the Oak Park Studio employees, working to complete many unfinished Wright commissions after Wright left them all behind and went galavanting off to Europe with his client and paramour Mamah Borthwick Cheney. Under the chaerge and guidance of Herman Von Holst, with the help of contracted designers Marion Mahoney and Walter Burley Griffin, Isabel and John Van Bergen brought what work they could of Wright’s to completion, then Isabel locked the doors of the Oak Park Studio, thus closing the productive Oak Park years of Wright’s career.

Those last months would have been extremely trying, because Wright was mostly incommunicado in his sylvan country retreat in Fiesole, outside Florence, Italy. Mamah and he sequestered themselves there, he, working on dreamy sketches for a prairie style house and studio situated in Italy (never realized), and she, translating the work of her inspiration, feminist Ellen Key. As always, Wright was quite cavalier about matters of business and payment to the

So, what did Isabel do, once the Oak Park Studio was closed forever?

Isabel Roberts states in her AIA application that she served one year or more as a draftsman in the firm of Gunzel and Drummond, Architects, circa 1915-1916. Her Chicago area work, in addition to that, in the late teens of the 20th century is not yet known. Evidence indicates, however, that among her projects was architectural work designing for the prefabricated kit house company Gordon Van Tine. One of their models (2617) is a direct copy of the K. C. DeRhodes House, slightly simplified for economy's sake. For more about this, see my September 23, 2012 article on this blog entitled: Prairie Style House Near Mount Dora, which explains the house and its known example in Eustice, Florida. The Gordon Van Tine models were well-designed and consisted of sturdy materials that continue to serve their owners 100 and more years later... They also brought the Chicago Style (i.e. Prairie Style) to places where such aesthetics were otherwise unavailable. You will find Gordon Van Tine models all over the USA. Their origins are to be found in the architects of the Chicago School, including Isabel Roberts.

The Roberts family began visiting Central Florida in the winter of 1915-1916, perhaps earlier. They divided their time between Chicago and St. Cloud for several more years, spending the cold northern winters in sunny St. Cloud.

The history of St. Cloud is fascinating. It was designed as a community for veterans of the Civil War, both from the south, but even more so from the north. Many of the streets bear the names of the states that fought in the conflict. Historians will point out that the best located streets all bear the names of northern states. Civil War veterans flocked to St. Cloud, and built what we would call Adirondack tent type dwellings at first, that is, wooden platforms on which canvas tents were erected. As time and funds permitted, these were replaced or converted into more permanent dwellings, often of a bungalow type.

There was a busy and active collection of civic organizations, promoting the city and sponsoring activities for a wide range of interests. There was a seasonal population as well as a year-round population. Snowbirds found their way from the frozen northland to enjoy the salubrious winter climate of Central Florida. Many of them decided to make St. Cloud their only residence, eschewing the miserable grey skies, icy sidewalks, and relentless winter snow of places like Chicago.

Frequently, as the St. Cloud society news columns report, the William Drummond family were fellow winter residents / vacationers with their friend, and colleague, and River Forest next door neighbor, Isabel Roberts, and her mother.

But, all was not well in River Forest. Mary was ailing. The St. Cloud Tribune offers this insight:

"May 9, 1918 - Mrs. John Somerville [Charlotte Roberts], who has been called to Chicago on account of the illness of her mother, returned here last Saturday evening and has again taken up activities with the local Red Cross Chapter."

In 1919 Isabel Roberts and her mother Mary moved permanently to St. Cloud, Florida. So, a decade after the Isabel Roberts House was completed, Mary and Isabel had left it, and River Forest, behind forever.

Isabel’s sister Charlotte and her husband John B. Somerville (December 31, 1840, Glasgow, Scotland - September 27, 1928, Mason, Iowa; buried Rose Hill Cemetery) were by that time well-established residents and highly respected citizens of St. Cloud. John Somerville was a generation older than Charlotte, and related by marriage to Mary Harris Roberts' Glover uncle, Robert Glover (Isabel and Charlotte's great-uncle), whose wife Mary Somerville was the sister of John Somerville. According to family historian Sarah Hogoboom, the family connections go back to the 1830s, where the Harrises, Glovers, and Somervilles were all residents in Utica, New York. John saw military service in Washington DC during the Civil War and had been one of the soldiers who guarded Lincoln's casket. Following the war, he was given land in St. Cloud, as a Civil War veteran, in thanks for his service. He was also given land at Cape Canaveral. After John Somerville died in 1928, while on a visit to family and friends in Mason, Iowa, Charlotte inherited the land at Cape Canaveral, and after her death in 1933, Isabel inherited it. The government was providing payments of $10,000 at certain intervals, and evidently, some man came upon the scene and was stripping Isabel of these payments in the years before she died. (More about the land at Cape Canaveral, later in this article).

Isabel and Mary Roberts lived with the Somervilles, initially upon their move to Central Florida. The four of them are enumerated in the US census of 1920, (which was taken between January 5 and February 5) in the Somerville household on Missouri Avenue. "Isabelle" who is by now age 48, gives her profession as "Architect".

Their very modest bungalow house is shown as it looks today, below:

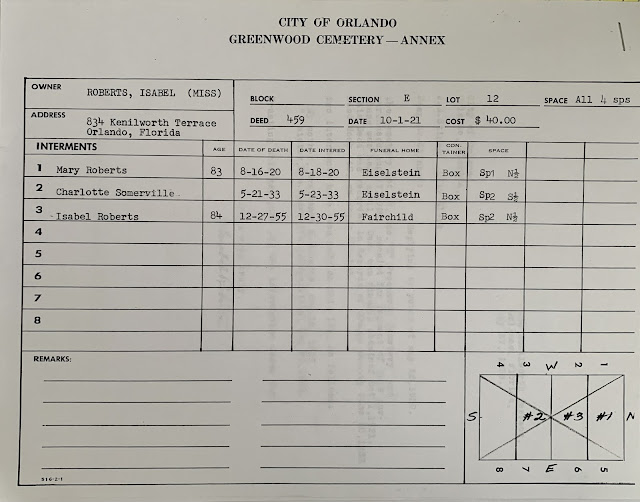

Mary Roberts died at her daughter Charlotte’s home in Florida, on August 16, 1920, having suffered the lingering effects of the influenza pandemic. Mary Roberts was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Orlando. Her grave site is known, but it remains unmarked. (Later both Charlotte and Isabel would be buried alongside her).

Mary Harris Roberts' obituary appeared in the August 19, 1920 St. Cloud Tribune:

"Mrs. Mary Roberts - On the afternoon of August 16th, Mrs. Mary Roberts passed away at the home of her daughter Mrs. John Somerville. Mrs. Roberts has been in failing healthy for some time, never having fully recovered from the "flu" which she had in the winter. She had spent several winters here in St. Cloud, coming here the last time two years ago from River Forest, Illinois.

Mrs. Mary Roberts was born in Prince Edward Island in 1836. In her early teens she came with her parents to New York State, where she lived until she was married in 1867 to James H Roberts of Utica, NY. After a few years in different places, they located in South Bend, Indiana, where she lived until the death of her husband in 1907.

Mrs. Roberts was a devout Christian, a member of the Presbyterian church from childhood and always a staunch believer in the faith. She is survived by two daughters, Mrs. John Somerville of St. Cloud and Miss Isabel Roberts of Orlando.

The funeral service was held at the home of Mrs. Somerville on Wednesday afternoon. Dr. Silas Cooke officiating, and the body was laid to rest in the Orlando cemetery."

A sad chapter in their lives, and especially so for Isabel who was so close to her mother, and who had lived with her for most of the years since James' death in 1907.

Once she was committed to life in Florida, Isabel Roberts went into architectural practice with Ida Annah Ryan, who was the first woman in the United States to earn a masters degree in architecture, from MIT. At the time of the 1920 US census, Ida had not yet relocated to Central Florida; she appears twice in the census (taken between January 5 and February 5) - in Waltham (she is listed in her parents' home, as an architect), and in Washington DC, where she is a lodger and a draughtsman for the US government.

One of the unanswered questions of the story of Isabel Roberts and Ida Ryan is: How did they first meet?

There are several likely possibilities, but none of these has yet been proven.

The first possibility is that they met in Saint Cloud. When Isabel was there on vacation, along with her mother, and their friends and neighbors the Drummonds, somewhere in the period between 1915 and 1919. It’s quite possible that Ida was also in Saint Cloud, if the information we have about her designing the railroad station there is correct. The social life in Saint Cloud was quite busy, there were many winter visitors to Saint Cloud, and as prominent citizens of Saint Cloud Charlotte and John Somerville would’ve been the center of much of the activity, so of course it would also have included their relative Isabel. Nothing would have been more logical than, hearing that another woman architect was in town, that the two would had been introduced to one another there.

A second possibility might be a connection between the two women forged by Marion Mahony. Both Marion and Ida had graduated from the architecture program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Thereafter, Ida had formed a successful architectural partnership in Waltham. And through the good graces of her cousin Dwight Perkins, Marion was made aware of Frank Lloyd Wright and he of her. Leading to her working for Wright in Chicago. It is conceivable that at some point, after Isabel had also joined the Oak Park studio staff, that Ida traveled to the Midwest and visited the Oak Park studio to see her friend Marion, and to see what was happening there, hosted by her MIT fellow alumni.

While both of these seem to be the leading possibilities, other scenarios might also have some merit.

For example, we really don’t know where Isabel was and what she was doing in the years between when she graduated from high school in South Bend in 1890, and when she began her architectural studies in New York City a decade thereafter. There’s one report that she was an art teacher at this time, but no location has yet come to light. Was she an art teacher somewhere in the Boston area? Did she meet Ida Ryan, whose practice specialized in school design, then? We just don’t know.

Another possibility is that there may have been a connection between Ida Ryan and Masqueray, perhaps forged because of Ida's professor and fellow Franco-American at MIT, Constant Despardelle. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that Ida may have visited the Atelier Masqueray, and there met Isabel. But again there is no evidence to prove or disprove such a theory.

In addition to these very real possibilities, one could create other possible scenarios. Any one of which might be true. Keep in mind that Ida was active in the suffragette movement. It is an open question whether or not Isabel was. She was an independent-minded woman, with a chosen profession that was dominated by men. There may have been both personal philosophical reasons why she might have felt affinities with the suffragette movement. If so, was it possible that through that movement she and Ida met?

We have a letter from Ida Annah Ryan - who had been a successful architect in Waltham, Massachusetts - who responded to her Massachusetts Institute of Technology Class of 1905 "annual" praising what she found when she relocated in the early 1920s. It reads as follows:

IDA ANNAH RYAN

ISABEL ROBERTS

Architects

222 South Orange Avenue

Orlando, Florida

Glad to know of a revival of interest in the Class of '05, particularly in a State where there are so few M.I.T. architects. Henrietta C. Dozier of Jacksonville and Mr. Adams of Tampa, president of the State Architectural Association, being the only two discovered to date. Florida is the new pioneer state in the United States, has the most equitable climate, except California and is three times as accessible to the East and Middle West. We have no dull times here - building has continued marvelously through it all - towns spring up like mushrooms, almost, in 90 days. Good roads are increasing every day and afford the best means of approach to all parts of the Site. Natural resources are waiting to be developed. No one knows how many or to what extent. Hundreds of miles of wild country are waiting for settlers. Parts of the Everglades have been drained and some of the richest truck soil in the world uncovered, I am glad to be here, and hope to help put this new country in its rightful place on the map. Cordially, Ida Annah Ryan (1905)

*****

As the firm Ryan and Roberts, they occupied several locations for their studio. According to their 1921 stationery, their primary place of business was located at 1 McNeil Davies Building, in Orlando, with two alternative addresses also listed, Edgewood Place, in River Forest, Chicago Illinois, and 19 Hammond Street, in Waltham, Massachusetts. This suggests that both women had retained their previous locations while establishing their new practice in Central Florida. It also suggests that they were completing remaining projects in Chicago and Waltham as they began their new lives in Orlando.

Ida Annah Ryan was already an architect of note with many successes to her name. She was born on November 4, 1873, at Waltham, MA. Ryan became the first woman to earn a master of science degree from MIT and also the first woman in the United States to receive a master's degree in architecture.

In a lively practice in the Waltham area, Ryan launched the first women's architectural practice in the United States, showing a particular concern for the design of modest housing. In 1909,[10] Ryan added fellow MIT graduate and women’s rights suffragette and activist Florence Luscomb to her practice, making this one of the first all-women’s architectural practices in the United States.[11] In February 1913, Miss Ryan was appointed the superintendent of buildings and grounds and buildings inspector for the city of Waltham.

Ryan was active in the women's suffrage movement, a member of the Waltham Equal Suffrage League and the Political Equality Association of Massachusetts. When the United States entered World War I, Ryan gave her services without charge in designing and decorating the Army and Navy Canteen on Boston Common. Ryan offered her services to the government in Washington, D.C., and was the first woman employed in the War Department (in the gun carriage section).

Ryan began her association with the Central Florida area while still in practice in Massachusetts, designing the Atlantic Coast Line railroad depot in St. Cloud (1917)[21] and the Unity Chapel of Orlando (built in 1913, remodeled by Ryan and Roberts circa 1920). Throughout this time, Ryan’s many attempts to join the Massachusetts chapter of the American Institute of Architects were rebuffed solely because she was a woman. A lengthy correspondence regarding her application, the discussion of it by the AIA leadership, and their refusal, is in the AIA archives.

You may read much more about Ida Annah Ryan in my article devoted to her, first published on this blog on April 1, 2022, based on research I began in 2008.

We need to note that even as Ryan and Roberts were making a name for themselves in Orlando, there arose controversy. Objections were raised regarding Isabel’s use of the title architect, as the term was becoming protected professionally.

To address these objections, Isabel applied for AIA membership. In the application, she gave her architectural training with E. L. Masqueray, and her employment with Frank Lloyd Wright, and with Guenzel and Drummond, as evidence of her architectural experience. Several architects of note from Isabel’s Chicago period wrote letters of recommendation on Isabel’s behalf, to help clarify her qualifications. These letters are now in the AIA archives at The Octagon, the AIA's Washington DC headquarters. The writers were: Herman von Holst (who oversaw Wright's practice when he decamped to Europe with Mamah Cheney). John Van Bergen (Isabel's fellow faithful staff member at the Oak Park Studio, who went on to have a remarkable career as a gifted architect). And the most telling letter was written by Frank Lloyd Wright himself, as follows:

Well! That seems about as clear as possible, even down to giving Isabel Roberts his highest accolade of spelling "Architect" with a capital "A". No mater how Wright would later speak of Isabel's work in the Oak Park Studio, this 1920 letter of reference clarifies his view of it, prior to the time in which he became unduly committed to enlarging his accomplishments by dismissing the contributions of his architectural staff.

It was arranged through the good graces of several Orlando area architects for Isabel to take the AIA qualifying tests. A date and location were set. But when the day arrived, Isabel got cold feet and she did not take them. In reference to her not appearing to take this examination, her second cousin Bill Hogoboom told me when we met together in 2009 that Isabel was a bit "ditzy" (his word, not mine). That description does not fit the other things we know about Isabel's life accomplishments, and I almost left it out of this article, but in all fairness, decided that to share it might provide some helpful insights. The chief meaning of the word is "scatterbrained", which also does not describe a woman who designed intricate geometric stained glass, innovative suburban homes, and also kept a busy architectural practice well-organized. One can characterize Isabel as artistic, creative, well-educated, smart, businesslike, faithful, adventurous, able to hold her own in a profession dominated by men, and possessing a refined aesthetic sensibility. But "ditzy"?

And so, Isabel did not qualify as an AIA member, then or thereafter. But she continued to work in partnership with Ida, and their practice continued to be called Ryan and Roberts. They continued their architectural partnership, but with Isabel listed as a landscape architect, a field that was at that time even less strictly defined than the profession of architect. To those who insist that to be an architect one had to be a member of the AIA, please, remember that Frank Lloyd Wright was

Ryan and Roberts, Architects, became a force to be reckoned with in the greater Orlando of the 1920s. Their work included fine private residences, a luxury apartment building, a private sanitarium, a municipal library, a hotel, a bank, a funeral home, a number of churches, and an entire seaside subdivision. They were commissioned to create public structures that helped to define the communities in which they were built, including the Tourist Club of St. Cloud, and the trademark building for the City of Orlando from the 1920s through the 1960s: the Lake Eola Bandshell.

As the firm of “Ryan and Roberts”, they were among no more than a dozen architecture firms active in Orlando in the 1920s. Their business is listed under the heading “Architects” as Ryan and Roberts in the 1925 phone book (see illustration below), and the 1926 and 1927 Orlando City Directories at their Kenilworth Terrace address. One of only 10 so listed in 1926, and 12 firms so listed in Orlando in 1927.

The other Orlando architerual firms included:

Frank L. Bodine, Fred E. Field, David Hyer, Murry S. King, George E. Krug, Howard M. Reynolds, Frederick H. Trimble and Percy P. Turner. And one of 12 firms so listed in Orlando in 1927, which included Maurice E. Kressly. All are outstanding regionalist architects. Together, their works form a wonderful legacy in Central Florida.

(You can read about each of these firms in the Wikipedia articles about each, all of which I researched extensively and posted initially, the early 2000's).

A list of the other firms at work in Orlando in the 1920s serves to help round out the positive collegial atmosphere they fostered, as they sought to create a type of architecture that was suited to the Central Florida environment. What emerged was a large body of work from each of these architects that had as its inspiration Spanish Colonial architecture.

This was entirely in keeping with the history of Florida, where the first European settlement, and one of the oldest cities in the United States, was founded by Spanish settlers at St. Augustine. Very few houses from that first Spanish era survive in St. Augustine, and so, there were few architectural precedents to be seen and studied there.

Much more available were the Spanish Colonial buildings that survived on the West Coast and in the desert Southwest. By 1920, these buildings had become the focus of many architects throughout the nation. They were given even greater attention as the result of a series of valuable scholarly articles authored by Rexford Newcomb, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Illinois, published monthly in a year-long series in "The Western Architect", a professional journal that was read and discussed by architects everywhere. The articles were considered cutting edge. They presented authentic Spanish Colonial architecture in photos and measured drawings, with all its simplified forms, in stucco, with restrained use of ornament, often with either flat roofs or with barrel tile roofs, and parapets that were boldly geometric.

The Orlando Group of architect found these to be entirely in keeping with their goals for a Florida architecture. As the decade progressed, they implemented these goals in public and private buildings that have come to be among the most highly prized features of Central Florida's rich architectural heritage.

Eager to find a way to describe their new Florida architecture, they held a contest to bring about a name for the type of architecture they were striving for. The chosen entry was "Spaniflora".

As the 1920s progressed, the Central Florida visual environment became more and more "Spaniflora". Many of the buildings of that time have not survived the one hundred years to the present, but enough of them have survived to serve as examples of the collegial efforts of the Orlando Group.

Fine examples of "Spaniflora" architecture remaining from these architects include:

Frank L. Bodine, the Milner-Rosenwald Academy, 1560 Highland Street, Mt. Dora, Florida - 1926

David Hyer, "O-Po-Le-O" ("House Between the Waters" in the Seminole Language) The Grace Philips Johnson Estate, 1005 Edgewater Drive, Orlando, Florida, 1928. This is the best situated and finest Mediterranean Revival mansion in Central Florida, on the isthmus between Lake Concord and Lake Adair, with sweeping views towards downtown Orlando. Hyer worked in the Orlando area from the mid 1920's until November 1935, when he returned to Charleston SC. While working in Orlando, James Gamble Rogers II worked in association with him. An example of the Hyer / Rogers II association is the Norman French style John H. Huttig Estate at 435 Peachtree Road, on the south shore of Lake Concord in Orlando. The Grace Phillips Johnson House is shown below.

Murry S. King, Park Lake Presbyterian Church, 309 East Colonial Drive, Orlando, Florida, 1924. (Pictured below).

King is widely and rightly considered the dean of the 1920s Orlando Group of architects; he was a friend and colleague of Ryan and Roberts, and in his Spanish Colonial Revival work, great affinities can be seen between his aesthetic and theirs. Indeed, all of the 1920s Orlando architects were of a similar mind, as to the type of architecture that they believed best suited the Central Florida climate.

It is important to mention that this church is only a short walk from Isabel and Ida's home and studio on Kenilworth, in this same Park Lake neighborhood. Isabel was a member of this congregation after she belonged to the St. Cloud Presbyterian Church and First Presbyterian Church of Orlando.

Recent research has brought fascinating information to light about Isabel's connection to this congregation.

My long-time friend and college, the church's co-pastor, Helen Debevoise, has written to me on June 29, 2022, to share the following, in response to my asking her whether the church had any information about Isabel.

"Here's what I found in our official records. Miss Isabel Roberts was received by transfer of letter on October 7, 1925, from First Presbyterian Church Orlando. She was in the first group to join Park Lake at its beginning. Dedication Sunday was October 14, 1925. She may have been listed as the 159th member to join. I need to confirm that notation. A record shows she died December 27, 1955.

"Dan" (Helen's husband and co-pastor of the church) "must be referring to her when he said, 'I heard Frank Lloyd Wright's secretary was a member of Park Lake'. Dan has read a letter from the Wright Foundation requesting information about Isabel Roberts. ...

"There's a 1926 church directory listing her in Circle Number 5" (Circles are women's study and prayer groups in the Presbyterian Church). "Her address is Roberts and Ryan, S Orange Ave. Her name is spelled 'Isabelle'. Larger Church directory lists her address as 1240 Kenilworth Drive." (that is, the Ryan and Roberts Home and Studio in the Park Lake neighborhood).

Wow!

This is exciting new information. Thank you, Hellen, for sharing it!

I am reminded anew that Isabel was a devout woman of faith and a dedicated lifelong Presbyterian. Notice how she was intentional about maintaining her membership in the Presbyterian Churches that were nearest her home, whether as a young woman in South Bend, or in her successive moves within Central Florida - St Cloud, Orlando, and Park Lake Presbyterian Churches.

I suppose Park Lake would call her a Charter Member. The church was brand new when Isabel transferred her membership from First Presbyterian in downtown Orlando. And being among the "first group to join" that is what I would call her.

Those familiar with Orlando geography and history will tell you the Park Lake neighborhood was a new and attractive northern suburban development around Park Lake in the 1920s. Isabel and Ida not only built their own home and studio there, they also owned other pieces of property there, and designed other neighborhood homes as well. (How many is still being discovered). The neighborhood was upscale then, and it remains so today, one of Orlando's most desirable neighborhoods for professionals and their families.

I must say that I am intrigued - and more - that the Wright Foundation KNOWS that Isabel was a member of the Park Lake Presbyterian Church, and has even bothered to correspond with the church about her. (!!) Where Isabel's work is concerned, certainly, this is not a main avenue of research. It is an obscure tidbit of information. That they have asked, indicates that much more research has been undertaken by the Wright Foundation, else why would they even know enough to ask the question?

Curiouser and curiouser.

It shows that there is focused and detail oriented research going on from that quarter, which as yet (mid-2022) has not been mentioned or published by them. They most certainly have read my 16 years worth of research, and are trying to build upon it. And they know much more about Isabel being an architect than they are letting on.

Perhaps, at long last, the architectural history pundits and Wright devotees who have long insisted that Isabel was' just a secretary', will acknowledge that she was in fact an architect in her own right, as evidenced by her academic training in Manhattan, her considerable experience in the Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright, and in her own highly successful architectural practice with Ida Annah Ryan in Orlando.

Let's hope so.

Isabel's recognition from that quarter is many, many decades overdue.

Howard M. Reynolds, Marks Street School, 99 East Marks Street, Orlando, Florida, 1925; and Cherokee School, 500 South Eola Drive, Orlando, Florida, 1927.

Frederick H. Trimble, Vero Theater, 2036 14th Avenue, Vero Beach, Florida, 1924.

Percy P. Turner. 803 Lake Adair Boulevard, Orlando, Florida, 1925, (Below):

Maurice E. Kressly. Casa de la Esquina, Palmer and Alabama Drive, Winter Park, 1922. And Casa Alameda, 754 Seville Place, Orlando, Florida (Below):.

Arthur Beck (1899-1990) Casa Caprona, Ft. Pierce, Florida - 1926:

Mention must be made here of the disparaging comments by some architectural historians regarding the Orlando Group of architects (and architects elsewhere) who were designing their buildings in "styles" which were not, therefore, entirely new forms.

First, it is important to remember that by the time WWI was over, so was the Chicago Group's Prairie Style movement. It had had notable success in Chicago and in the upper midwest. Its ideas had been spread by publications such as "The Western Architect" and the anthologies of residential architecture edited by Hermann V. Von Holst. The ideas had been spread by the relocation of some of its chief proponents elsewhere (such as Irving Gill, to southern California). But as the public interest in the prairie school idiom waned, there arose regional responses that took even the best-known practitioners of the movement in new directions, which were almost exclusively connected to or inspired by historic architectural styles.

For example, Wright associated architects William Drummond and John Van Bergen, whose prairie style designs are second to none, thereafter each created successful and pleasing works in Colonial Revival and Tudor styles in the same Chicago neighborhoods where once they designed prairie style residences, sometimes next door to each other. Another architect from the Oak Park Studio. Barry Byrne, developed his own distinctive architectural style which is highly personal and has affinities to the Art Deco movement.

Off in Australia, two of Wright's most creative former employees, Walter Burley Griffin and Marian Mahoney Griffin elaborated upon ideas that they had begun in Iowa during their independent USA practice, and they went on to become the darlings of a continent, where they are still lionized a century later, and deservedly so.

The aforementioned Irving Gill, who had worked alongside Wright at Adler and Sullivan, and had been criticized by Wright for dressing as he did, in the Elbert Hubbard (or Little Lord Fanutleroy!) artsy style of clothing, left most of the identifiable Chicago School ideas behind, when he moved to Southern California. And, there he created what can be called the first modern architecture with a poetic soul. Some of the work by Irving Gill is remarkably similar to some of the work that Ryan and Roberts did.

Another Oak Park Studio employee, Albert McArthur, devised textile block construction for the Arizona Biltmore - a work of which McArthur was the architect, and which he designed. However, Wright enjoyed giving himself credit for it, as have many who followed his lead. (Wright asked McArthur for permission to use a modified version of the Arizona Biltmore blocks for his own work in California in the 20's).

Moreover, Frank Lloyd Wright abandoned the prairie style for his experiments in Mayan Revival in California, his take on Art Deco (Johnson Wax) and International Style (Fallingwater) works of the late 1930s, and his Usonian and flights of fancy forms of his old age.

To chastise any one of these for not continuing to work in the prairie school idiom is to open all the rest to similar unwarranted criticism

Ryan and Roberts began designing buildings together just as the demand for prairie style buildings was waining. Several of their works have themes that can be traced back to the prairie style, including the Veterans Memorial Library, the Dodds Residence, and the Lake Eola Band Shell. The Veterans Memorial Library would be right at home in a small town setting in Wisconsin or Minnesota. The Dodds Residence could hold its own with all the other prairie school houses in the Chicago suburbs. And the Lake Eola Bandshell could just as easily be a boathouse on Delaven Lake. But as the 1920s progressed, they created landmark buildings in a "Spaniflora" variety of Spanish or Mediterranean Revival style in Central Florida, some of which still stand today.

This list of their works is incomplete and you can help expand it, by sharing with me information about other structures you understand to have been designed by Ryan and Roberts:

Veterans Memorial Library - 1012 Massachusetts Ave., St. Cloud, Florida - Isabel Roberts’ brother-in-law, John B. Somerville, served on the building committee, a connection which resulted in Ryan and Roberts obtaining this commission. In 1922, an outline of what was desired was laid before architects Miss Ida Annah Ryan and Miss Isabel Roberts of Orlando. The plans submitted by these ladies were subsequently accepted. The architects insisted on a motto; Carlyle's, "The true university is a collection of books," was chosen. The building, although described at the time as being of Grecian style, is in fact reminiscent of the "jewel box" rectangular designs of many of the Prairie School small bank buildings of the upper Midwest by Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Purcell and Elmslie, and others. The library is constructed of hollow tile with stained stucco exterior, well-maintained, and still in use today. It now houses the St. Cloud Heritage Museum. The building is currently owned by the City of St. Cloud; however, the museum is operated solely by volunteers of the Woman's Club of St. Cloud, whose clubhouse is next-door. Although it is not a large building, it has a large presence due to the bold geometric lines of the main facade. Prairie Style themes in addition to the "box bank" massing include the grouped windows, the flat roof, the strongly defined cornice and window surrounds, and the use of casement windows broken into geometric panes. The symmetry and the central door also reflect the prairie style bank buildings. Some observers see a direct connection to lines of Unity Temple in Oak Park, in this little gem of a building.

Veterans Memorial Library - Dedication Day

L to R: John Somerville, Charlotte Somerville, Isabel Roberts, Unknown

The library was dedicated on February 11, 1923. Sixty members of the Grand Army of the Republicans forty members of its auxiliary, the Women's Relief Corps, marched to the Library for the flag-raising ceremony. After the ceremony, the club handed the building over to the city of St. Cloud.

Veterans Memorial Library, St. Cloud, Florida - Rear View

Veterans Memorial Library, St. Cloud, Florida - Rear ViewAmherst Apartments - 325 West Colonial Drive, Orlando, Florida - The Amherst Apartments were, for many years, Orlando’s most prestigious apartment address. Designed by Ida A. Ryan and Isabel Roberts in the Prairie Style and built in 1921-1922, it featured forty-seven apartments (although see the circa 1927 ad below that s ays 67) situated on park-like grounds overlooking picturesque Lake Concord.

Stylistically this building looks much like the competition design for the proposed German Embassy building by Guenzel and Drummond, which was designed while Isabel Roberts was working for that Chicago area firm (illustration below). The H shape plan, window patterns, three story height, restrained use of ornament, and general air of stability make the two designs cousins if not siblings.

The three story building was demolished in 1986; the “Fanatic” building (also now demolished) was for some years on this site, thereafter. Although the building is long gone, vintage post cards show it in some detail, and also indicate that it was a place of interest in its long history as the foremost residential apartment building in Orlando:

Tourist Club House - 700 Indiana Ave., St. Cloud, Florida. (demolished). This club house for the Tourist Club of St. Cloud was opened in the city park on December 3, 1923. Designed by Ida Annah Ryan and Isabel Roberts, it shows the influence of the Prairie School with which Roberts was associated. As designed, it is a rectangular structure with clearstory windows and a barrel-roofed auditorium.